What do we know about the Old English Celtic and Anglo-Saxon calendar? Here are the historical sources.

According to Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79), Gaulish Druids began the month on the sixth day of the moon (basically the first quarter); no other source specifies the start date.

John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S., H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A., Ed.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D16%3Achapter%3D95

“Fifth day of the moon” appears to be an often-repeated mistranslation; the latin is sexta luna, not quinta luna:

See also:

https://archive.org/stream/naturalhistory04plinuoft#page/548/mode/2up

Tacitus (c. AD 56 – c. 120) says that the Germanic people assembled at new or full moon, and reckoned by nights.

Alfred John Church, William Jackson Brodribb, Ed.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0083%3Achapter%3D11

The Venerable Bede (672/3 – 735) described the Old English calendar in some detail.

Faith Wallis

The next several chapters describe the “course of the moon” through the zodiac, suggesting that he may be describing sidereal months, based on constellations; but the addition of a thirteenth month in embolismic years indicates that the months are in all likelihood synodic, based on phase.

He begins by associating each month with a Latin equivalent, but then describes a lunisolar system of 12 or 13 months in four seasons, then mentions an older system of two seasons.

A solar year does not contain an even number of lunar months, so some years need an extra month to stay in synchronization with the seasons. He does not describe the details of when the extra month was added.

This sounds like the old insular Celtic calendar which would have preceded the Anglo-Saxon one. The phrase “full moon of that month” seems to imply that months in Bede’s time did not start on the full moon. But he does not come out and say when months actually started.

Guili is Yule, described as the solstice; it appears to be a pivotal date. The calendar is evidently lunisolar: lunar months anchored to a solar event like the solstice.

So months are lunar; what about solar holidays, the solstices, equinoxes, and cross-quarter days?

The solstices and equinoxes have been known since antiquity; Bede has already mentioned the winter solstice.

Most of what we know about their observation in Celtic or Anglo-Saxon times is based on tradition and “cultural fossils.”

The English quarter days (also observed in Wales and the Channel Islands) are close to the solstices and equinoxes:

Lady Day (25 March)

Midsummer Day (24 June)

Michaelmas (29 September)

Christmas (25 December)

The cross-quarter days are four holidays falling in between the quarter days: Candlemas (2 February), May Day (1 May), Lammas (1 August), and All Hallows (1 November).

The Old Scottish Term and Quarter Days (Julian to Gregorian), prior to 1886, are close to the cross-quarter days:

Candlemas (2 February)

Whitsunday (15 May)

Lammas (1 August)

Martinmas (11 November)

More about celebrations:

3 Hutton, Ronald (8 December 1993), The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles, Oxford, Blackwell, pp. 337–341, ISBN 0-631-18946-7

4 Murray, Margaret. 1931. The God of the Witches.

5 Kinloch, George Ritchie. Reliquiae Antiquae Scoticae. Edinburgh, 1848.

Note also that the solstices are “midwinter’s day” and “midsummer’s day,” implying that the seasons begin on cross-quarters.

Discussion

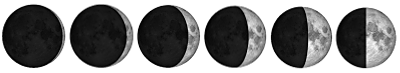

People who begin their months with the moon tend to begin their days at the same time, at sunset. Hence terms like fortnight (fourteen nights), and holidays that start on an “eve.” In antiquity, the “new” moon usually meant the first visible crescent (which appears after the dark of the moon, our astronomical new moon). But without an official observer in an official location, this reckoning is hard to standardize, much less predict. Pliny says that the Druids began their month on the sixth day of the moon. This is notable because the first quarter moon is very easy to recognize. The sighting of the first crescent depends on one’s vision and the atmospheric conditions, and even the full moon is not always easy to identify as it may look full three nights in a row. The sixth image below is the first quarter moon, and the preceding ones are each one day apart; you can see that the sequence begins with the “new” moon.

Depending on conditions, the first crescent moon tends to be visible by the first sunset 24-36 hours after the astronomical new moon; if you have good eyes and clear skies, it may be a number of hours sooner. If you are keeping track of the moon phases, the delay in sighting the first crescent would throw off the intervals between phases; someone who realized that the dark of the moon was actually the new moon might want to start the month on a more-identifiable phase.

It appears that months/moons were the basis of short-term periodic events such as community meetings and the mistletoe ceremony. They were synodic, with a thirteenth month added when needed, and began after the winter solstice. The big annual holidays were either solstices/equinoxes or cross-quarters, probably not both, although remnants of both still exist. (The eightfold wheel of the year is cool, but it is actually a modern syncretism.)

Bede says that when a thirteenth month was addd to the year, they called the year “Thrilithi” (three Lithas). But he does not give the month an actual name, other than to say that three months together bore the name “Litha”. Similarly, he calls the Yules “the months of Giuli.” At some point, possibly fairly recently, the double months were distinguished as Ærra Gēola (Ere Yule) and Æfterra Gēola (After Yule), Ærra Līþa (Ere Litha) and Æftera Līþa (After Litha). It so happens that if a third Litha is added after the first two, the month of After Litha may begin before Litha, the summer solstice. This doesn’t sound right, even though it is actually not a contradiction if “ere” is interpreted as “early” or “former,” and “after” similarly as “late” or “latter,” as in afterthought or afterburner. Be that as it may, I have named the thirteenth month “Middle Litha” (Middel Līþa ?) and placed it between the other two.

Making a “modern” Old English calendar

Should the calendar be based on observation, or mathematics? Sunset is fairly easy to recognize as long a you have a clear horizon. The first quarter moon is also easy to identify as described above. If it’s overcast, a mean synodic month is 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes, 2.8016 seconds; simple math may be used with this interval with fairly good long-term accuracy. Something like this plus the Metonic cycle also makes a lunar calendar that is reproducible over long intervals without the use of computers.

The ancients determined when to add months in embolismic years using the Metonic cycle or similar means; observational rules having to do with fixed events such as the summer solstice may also be used. Observational rules are inherently a little inaccurate because lunar months are not all the same length. But if you want a rule, here’s one. The winter solstice is 183.51 days after the summer solstice, and the mean synodic month is 29.53 days long. That means that there are about 183.51 / 29.53 = 6.214 lunar months between the summer and winter solstices. After Litha through Ere Yule is 6 lunar months. So if Ere Litha ends less than 6.214 - 6 = 0.214 months, or about 6 days and 8 hours, after the summer solstice, or before it, you will need a 13th month; add Middle Litha.

The solstices and equinoxes may be determined using observatories like Stonehenge, or instruments like equatorial rings that the ancient Greeks used; it takes a degree of doing and know-how.

Of course, if you want to generate an entire calendar ahead of time, you will need to use mathematics. High-tech computer algorithms may be used to determine any moon phase, solstices, equinoxes, cross-quarter days, and even sunsets anywhere in the world without difficulty. It is also easy to determine when there are thirteen moons of a given phase in a solar year. In short, you can do a much better job with computers, but some people like a hands-on approach. And they are not mutually exclusive; even though we now have cruise missiles, some people still attend revolutionary war re-enactments.

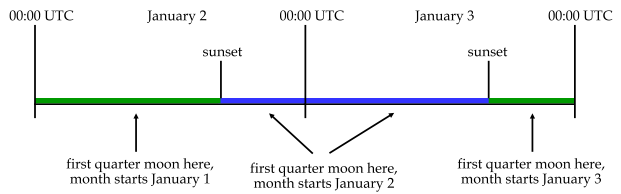

Should a lunisolar calendar be local, with everyone making their own observations and “doing their own thing,” or should there be a global standard? Mondern days are based on midnight at Greenwich, England. Lunar months could be based on sunset at Greenwich. Define “day” as sunset-to-sunset; the month would begin at local sunset on the Gregorian calendar date that begins a sunset-to-sunset day in Greenwich that includes the first quarter moon. That way, everyone everywhere on earth would start their month on the same date. These are actually the dates in parentheses in the calendar above. If you want to completely immerse yourself in the lunar calendar, you might even celebrate the holidays based on sunset days as well.

If you are curious, here are the sunset dates and times in Greenwich for the seleted calendar year:

Get your own local sunset times

See also:

The Sixth Night of the Moon

A Month by Month Guide To The Anglo-Saxon Calendar

The Anglo-Saxon Pagan Calendar

Observing Bede's Anglo-Saxon Calendar

The Coligny Calendar - Caer Australis

Common Holidays in Relation to Equinoxes, Solstices & Cross-Quarter Days

Early Germanic calendars

Celtic calendar